Primary Source Set

by Stephanie Hess, Digital Curator, Minnesota Digital Library

American Indians Arts and Literature People of Minnesota

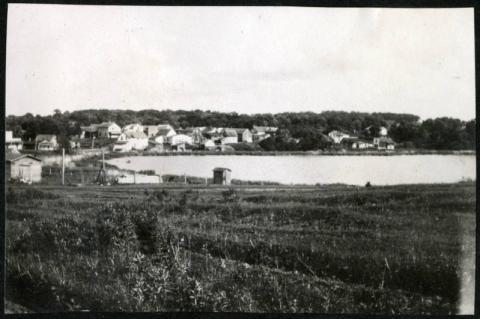

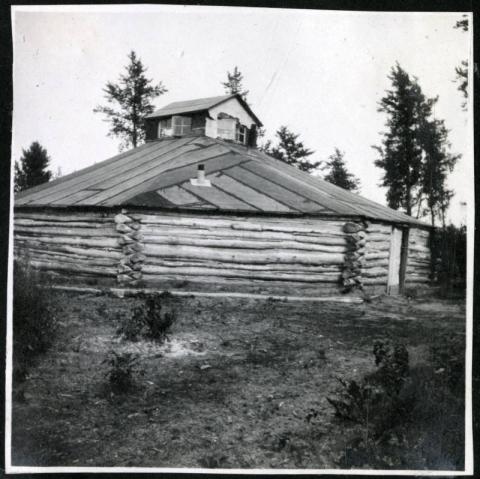

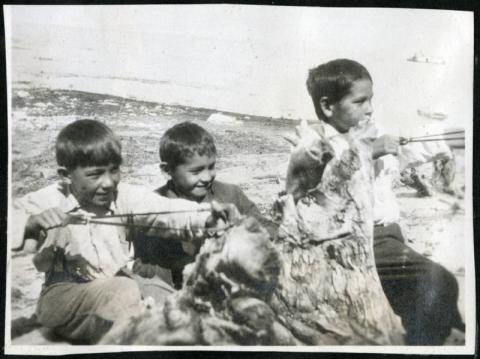

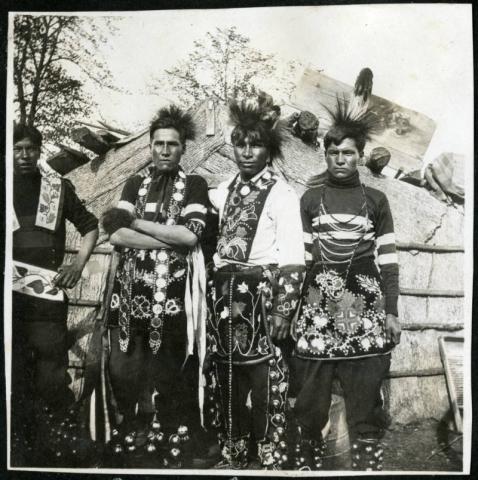

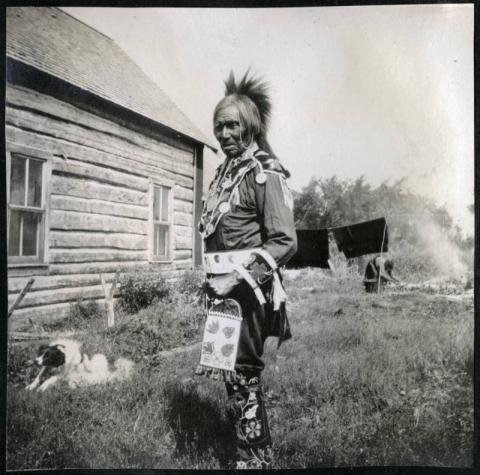

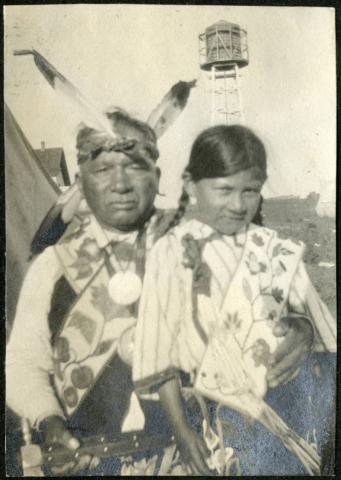

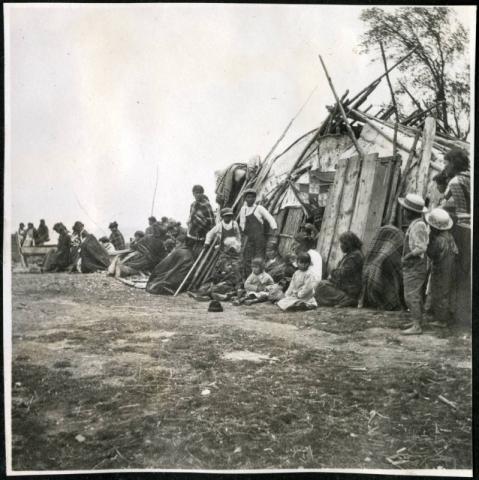

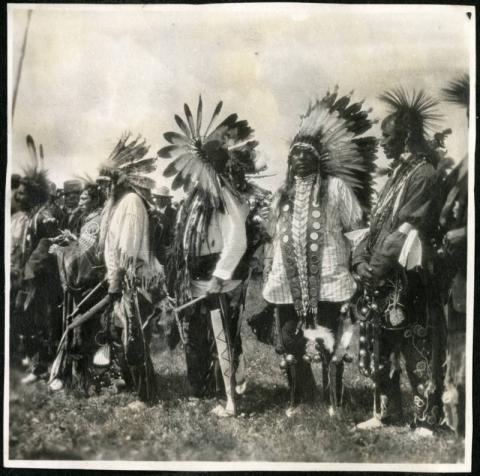

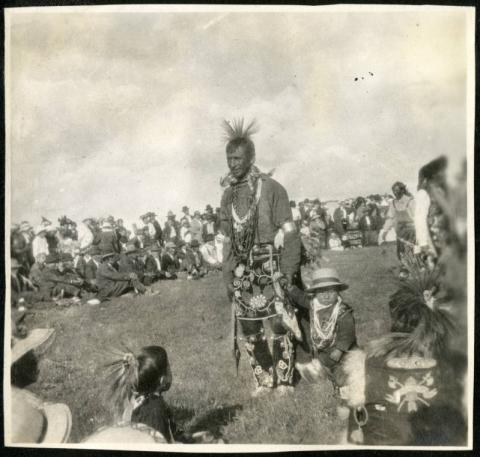

Stella Prince Stocker was a classically trained musician who moved to Duluth in 1885. She studied American Indian music and traditions among the Ojibwe people of Minnesota. She spent time at the White Earth and Red Lake Indian Reservations as well as Mille Lacs, Leech Lake, Nett Lake, and Fond Du Lac.

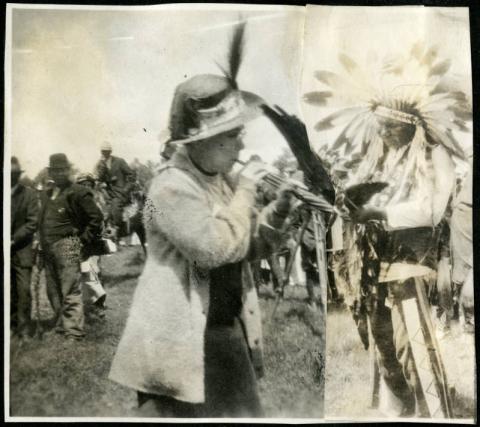

Based on her time among the Ojibwe, Stocker represented herself as an expert on American Indian culture and held exhibits and lectures on the topic. She also composed songs inspired by the music she encountered, including operas and a pageant called "Sieur DuLhut." For this pageant, she took research trips to the reservations and attended the Annual White Earth Celebration and Pow Wow in 1916.

The first annual White Earth Celebration and Pow Wow was held around 1872 in honor of the date when the Ojibwe relocated to the White Earth Reservation on June 14, 1868. Since then, people have gathered annually on or around June 14 to celebrate with traditional singing, dancing, and drumming. Pow wows like this are both social and spiritual events for Native communities but are open as well to visitors like Stella Stocker.

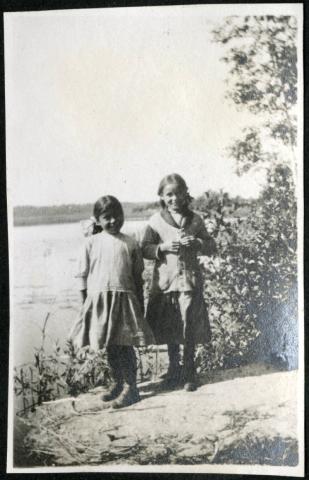

Stocker kept a diary and took photographs recording her Ojibwe visits during 1916 and 1917. She photographed parts of daily life as well as special occasions like the pow wow. The photographs are a rich source of information on early 20th century Ojibwe in Minnesota from a white woman's perspective. This Primary Source Set includes only a fraction of the photographs Stella took when learning from the Ojibwe in Minnesota. Use this link to view the complete Stella Stocker photography collection, part of the Northeast Minnesota Historical Collections housed in the Kathryn A. Martin Library, on permanent loan from the St. Louis County Historical Society.

Discussion Questions & Activities

- What are your first impressions of Stella Stocker's snapshots? What kinds of subjects caught her eye? Is there anything that surprises you in these photographs?

- Are these photographs representative and accurate depictions of Ojibwe culture and people? Why or why not? Consider also that it is not appropriate to photograph certain Anishinaabe ceremonies, sacred items, and other parts of their cultural heritage. Why do you think that is?

- What are the differences between casual snapshots and professional photography? Who makes these types of pictures? Why are they made? Who are they made for?

- Stella Stocker was not Ojibwe, but she spent a lot of time among their people and even participated in a naming ceremony, where she was given the Ojibwe name Mesquawigishigoque (Red Sky Lady). Do these experiences make her an authority on the Ojibwe tribes in Minnesota or do they make her a part of the community?

- We do not know exactly how the Ojibwe people felt about Stella and her documentation of their culture, but she did come into their community to collect things with a white settler perspective. Look up definitions of settler-colonialism to see how it has affected Indigenous people in the state, from land acquisition to cultural appropriation to contemporary erasure in society. Does this affect how you understand Stella and her work?

- These photographs show Ojibwe and Dakota people from the past, but Native people still live and thrive in Minnesota today. To learn more about contemporary Indigenous people, read books written by and about American Indians. Visit community events and exhibits at a Native community center or museum. Find more information and ideas here: Bdote Memory Map, Indigenous Representations eBook collection, Native Nations of Minnesota, Understand Native Minnesota, Why Treaties Matter, the Minnesota Historical Society’s Native American Culture & History page and their Our Home: Native Minnesota exhibit, and the Native Knowledge 360 education initiative of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian.

- How have things changed in terms of how Native American history has been taught in Minnesota since the early 1900s? How is it similar? What more do you want to know? Come up with a list of questions to research and find answers from a Native perspective.

- Use the Native Land tool (native-land.ca) to find whose traditional Indigenous homelands exist where you are and research the history of these people and tribes.

- Imagine you have been invited to visit a community of people whose culture is different than your own. Come up with a plan to get to know them and learn about their heritage. What is the value of learning about different people and cultures?

eLibrary Minnesota Resources (for Minnesota residents)

Bellfy, Phil. "Ojibwe." In Dictionary of American History, 3rd ed., edited by Stanley I. Kutler, 180-181. Vol. 6. New York, NY: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2003. Gale In Context: High School (accessed October 31, 2022).

Britannica Library, s.v. "Native American dance" (accessed October 31, 2022).

Britannica Library, s.v. "Native American music" (accessed October 31, 2022).

Britannica Library, s.v. "Powwow" (accessed October 31, 2022).

Duke, Winona. "White Earth (Reservation, Mississippi)." New Internationalist, October 1996, 35. Gale In Context: High School (accessed October 31, 2022).

"Everything an Indian Does is in a Circle: an introduction to the powwow; (based on a lesson from 'Powwow: Dancing the Circle,' a unit of study of the Denver Public Schools.--Karen D. Harvey)." Social Education 66, no. 4 (2002): S6+. Gale In Context: High School (accessed October 31, 2022).

McKosato, Harlan. 2015. “Powwows Then and Now.” Native Peoples Magazine 28 (2): 54–58 (accessed October 31, 2022).

"Pow Wow." Skipping Stones, September-October 2003, 8. Gale In Context: High School (accessed October 31, 2022).

Roy, Loriene. "Ojibwe." In Gale Encyclopedia of Multicultural America, 3rd ed., edited by Thomas Riggs, 359-373. Vol. 3. Detroit, MI: Gale, 2014. Gale In Context: High School (accessed October 31, 2022).

Additional Resources for Research

Indigenous Representations group. EBooksMN.org (accessed November 17, 2022).

Maus, P. "Guide to the Stella Prince Stocker papers, Identifier S3089." Northeast Minnesota Historical Collections, University of Minnesota Duluth Archives and Special Collections (accessed October 31, 2022).

“Ojibwe Pow Wows.” St. Louis County Historical Society (accessed November 1, 2022).

Peacock, Thomas. "The Ojibwe: Our Historical Role in Influencing Contemporary Minnesota." MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society (accessed October 31, 2022).

Sadie, Julie Anne; Samuel, Rhian, eds. The Norton/Grove Dictionary of Women Composers. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1994 (accessed October 31, 2022).

Stocker, Stella Prince. “Indian Diary From May 1916 [transcript].” From Stella Prince Stocker papers, S3089. Northeast Minnesota Historical Collections, University of Minnesota Duluth Archives and Special Collections (accessed November 1, 2022).

Stocker, Stella Prince. Sieur Du Lhut: Historical Play In Four Acts, With Indian Pageant Features And Indian Melodies. Duluth, Minn.: Huntley Printing Co., 1917 (accessed October 31, 2022).

Walaszek, Rita. “White Earth Celebration and Powwow.” Minnesota History, vol. 66, no. 3, Fall 2018, p. 95 (accessed October 31, 2022).

“White Earth Reservation, Minnesota.” In Honor of the People (accessed October 31, 2022).

Published onLast Updated on