Primary Source Set

by Greta Bahnemann, Metadata Librarian, Minnesota Digital Library, Minitex

Business and Industry Health and Medicine Science and Technology

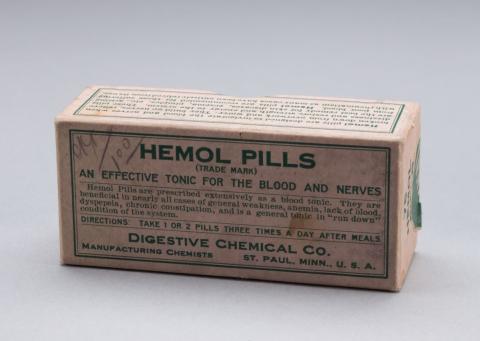

Throughout the nineteenth century and into the early twentieth century, Americans were inundated with myriad medicinal treatments collectively known as patent medicine. At a time when doctors and medical clinics were less common, especially in rural areas, patent medicines promised relief from pain and chronic conditions when few other options existed. The term “patent medicine” referred to ingredients that had been granted a government patent; but ironically many purveyors of patent medicine did not register their concoctions with the government. As a result, many competitors offered similar formulas and freely imitated each other’s products.

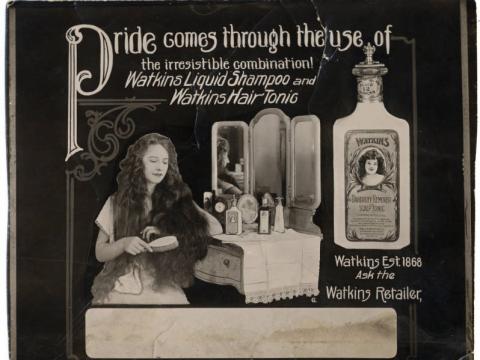

The story of patent medicine is multi-layered. It is about the phenomenon of Americans self-medicating with opiates, alcohol, and herbal supplements, as well as women’s health and healthcare options. It follows the evolution of advertising in America and the rise of chromolithography printing techniques and newspaper advertisements. Finally, patent medicine reveals dubious scientific knowledge during a time when germ theory was in its infancy.

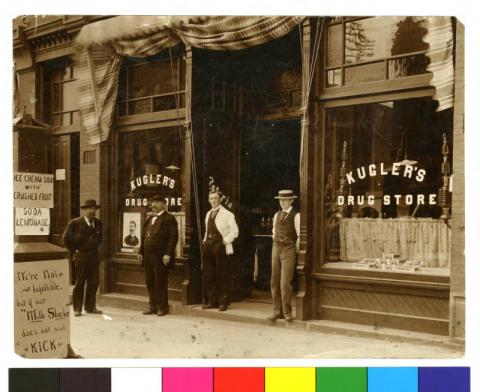

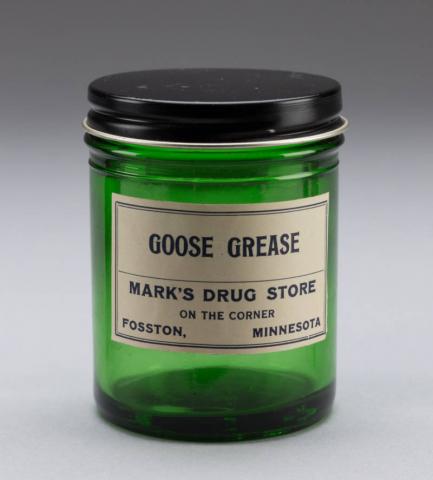

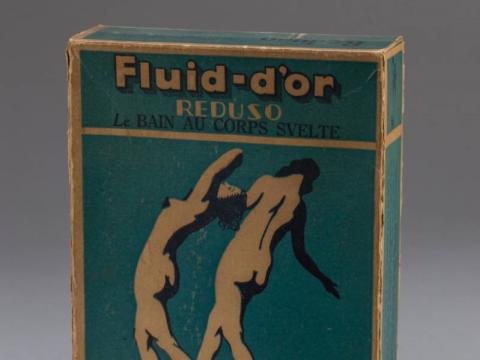

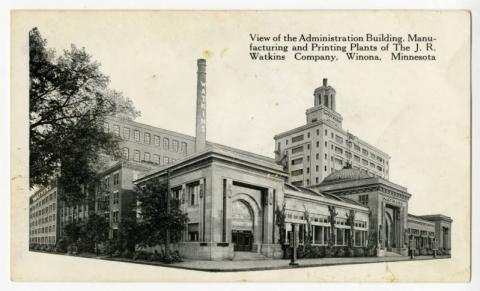

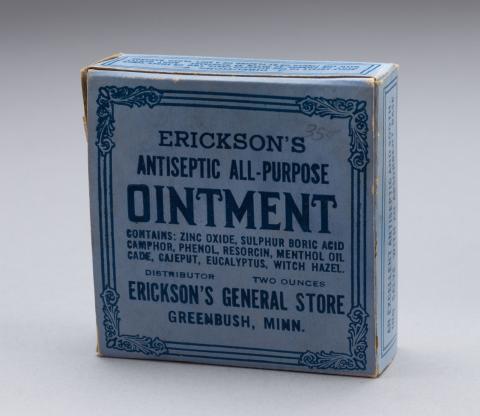

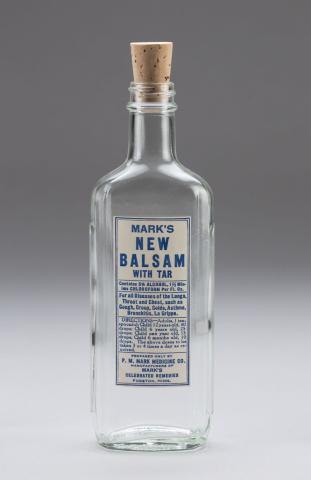

Many states became regional hubs for patent medicine production. A number of companies were based in Ohio, including Samuel Hartman’s Peruna Drug Manufacturing Company. Massachusetts was the home base for both Dr. Ayer and the Lydia Pinkham Medical Company. Minnesota was also part of this phenomenon. Home to the nationally-known J. R. Watkins Company, Minnesota also boasted a number of other producers, including Mark's Medical Company located in Fosston and the smaller Fluid-d’Or Company of Hibbing, Minnesota. Together these and other start-up companies helped to put Minnesota on the patent medicine map and contributed to the young state's growing economy.

This Primary Source Set is a companion to the online exhibition at the Digital Public Library of America.

Discussion Questions & Activities

- What different kinds of products are included in the general term "Patent Medicine"?

- Who were the intended consumers of these products?

- How similar or different do you think Patent Medicines are to contemporary products like dietary supplements and weight loss products?

- What responsibilities do companies have to their consumers to be honest about a product's benefits or side effects? What if a product contains an ingredient that can be addictive (such as opium or alcohol)?

- Working in pairs or small groups, have students look at advertisements for modern products that make dubious claims and promises. These products could include dietary supplements, weight loss remedies, hair loss cures, exercise and fitness equipment, etc. Ask students to research and discuss the concept of "truth in advertising." What do these products promise? What do these products deliver?

eLibrary Minnesota Resources (for Minnesota residents)

Advertisement for “Complete Female Remedy” Patent Medicine SYNOPSIS: Dr. Kilmer &..." American Eras: Primary Sources. Ed. Rebecca Parks. Vol. 1: Development of the Industrial United States, 1878-1899. Detroit: Gale, 2013. Student Resources in Context. Web. 17 Aug. 2016.

Aronson, Jeff. "Patent medicines and secret remedies." British Medical Journal 19 Dec. 2009: 1394+.Academic Search Premier. Web. 17 Aug. 2016.

Carnahan, Paul. “Patent Medicines.” Vermont Magazine, vol. 28, no. 1, Mar. 2016, pp. 68–76. EBSCOhost. Accessed 3 Oct. 2025.

Harbour, Glenn. “Doctor In A Bottle.” Antiques & Collecting Magazine, vol. 104, no. 11, Jan. 2000, p. 32. EBSCOhost. Accessed 10 Oct. 2025.

"Lydia E. Pinkham." Britannica School. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 21 Apr. 2008. Accessed 17 Aug. 2016.

"Patent medicine." World of Health, Gale, 2007. Gale In Context: High School. Accessed 3 Oct. 2025.

"Patent medicine." World of Invention, Gale, 2006. Gale In Context: High School. Accessed 3 Oct. 2025.

"Patent-Medicine Advertisements." American Decades, edited by Judith S. Baughman, et al., vol. 1: 1900-1909, Gale, 2001. Gale In Context: High School. Accessed 3 Oct. 2025.

"Pharmaceutical Industry." Gale Encyclopedia of U.S. Economic History, edited by Thomas Carson and Mary Bonk, Gale, 1999. Gale In Context: High School. Accessed 3 Oct. 2025.

"Regulating Medicine." American Decades, edited by Judith S. Baughman, et al., vol. 2: 1910-1919, Gale, 2001. Gale In Context: High School. Accessed 3 Oct. 2025.

Additional Resources for Research

"Balm of America: Patent Medicine Collection." The National Museum of American History. Accessed 17 Aug. 2016.

Bingham, A. Walker. The Snake-oil Syndrome: Patent Medicine Advertising. Hanover, Mass.: Christopher Publishing House, 1994.

Carson, Gerald. One for a Man, Two for a Horse: A Pictorial History, Grave and Comic, of Patent Medicines. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1961.

Cook, James Graham. Remedies and Rackets: The Truth about Patent Medicines Today. New York: Arno Press, 1976.

Eskew, Garnett Laidlaw. Guinea Pigs and Bugbears. Chicago: Research Press, 1938.

Hechtlinger, Adelaide. The Great Patent Medicine Era; or, Without Benefit of Doctor. New York: Galahad Books, 1974.

"History of Patent Medicine." Hagley Museum and Library. Accessed 17 Aug. 2016.

Morell, Peter. Poisons, Potions and Profits: The Antidote to Radio Advertising. New York: Knight Publishers, Inc., 1937.

Nostrums and Quackery; Articles on the Nostrum Evil and Quackery Reprinted, with Additions and Modifications, from the Journal of the American Medical Association. Chicago: American Medical Association Press, 1912.

Shaw, Robert Byers. History of the Comstock Patent Medicine Business and Dr. Morse's Indian Root Pills. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1972.

Published onLast Updated on